Finding Truth in Fiction: A Novel about a WWII Hero

September 1, 2019 in Library Corner

By Robin Jacobson.

In August 1940, Varian Fry bid farewell to his comfortable life in New York City and headed for Nazi-controlled France. He hoped to rescue 200 prominent artists and authors, many Jewish, who had fled German-occupied countries for France, initially a safe haven. Now these luminaries, all blacklisted by the Nazis, were in peril; the Franco-German armistice of June 1940 required France to “surrender on demand” any refugee Germany wanted. Fry’s mission was to spirit the luminaries out of Europe before they were arrested. By the time collaborationist French officials expelled Fry from France 13 months later, Fry had saved some 2,000 refugees. These included numerous 20th-century cultural icons such as artists Marc Chagall and Max Ernst and political philosopher Hannah Arendt. In recognition of Fry’s heroism, Israel’s Yad Vashem named him “Righteous Among the Nations,” the first American so honored.

In August 1940, Varian Fry bid farewell to his comfortable life in New York City and headed for Nazi-controlled France. He hoped to rescue 200 prominent artists and authors, many Jewish, who had fled German-occupied countries for France, initially a safe haven. Now these luminaries, all blacklisted by the Nazis, were in peril; the Franco-German armistice of June 1940 required France to “surrender on demand” any refugee Germany wanted. Fry’s mission was to spirit the luminaries out of Europe before they were arrested. By the time collaborationist French officials expelled Fry from France 13 months later, Fry had saved some 2,000 refugees. These included numerous 20th-century cultural icons such as artists Marc Chagall and Max Ernst and political philosopher Hannah Arendt. In recognition of Fry’s heroism, Israel’s Yad Vashem named him “Righteous Among the Nations,” the first American so honored.

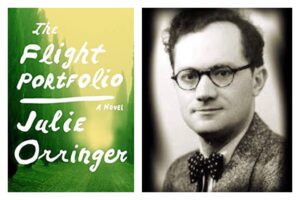

In her exceptional, deeply researched novel, The Flight Portfolio, Julie Orringer works within biographical and historical parameters to vividly imagine Varian Fry’s sojourn in France. This blending of fact and fiction to tell the story of a Holocaust hero has provoked some controversy, as discussed below.

What’s Known About Varian Fry

Born to an affluent Protestant family, Varian Fry (1907-67) graduated Harvard with a degree in classics, becoming a journalist and then a political-book editor. In 1935, he spent several months in Berlin, where he witnessed bloody anti-Jewish riots. The chief of Hitler’s foreign press division told him candidly that the Nazi party was divided on whether to relocate the Jews or exterminate them. Appalled, Fry reported the interview in The New York Times.

Five years later, Fry, only 32, returned to Europe as an agent for the private Emergency Rescue Committee, notwithstanding his lack of experience in refugee work, diplomacy, or spycraft. From a base in Marseille, he and his devoted staff helped refugees escape France by any means, legal or illegal. Fry pleaded for visas from the American consulate, but also arranged for fake passports and identity cards, bribes, and covert escapes over the mountains or by sea. A sympathetic American vice consul in Marseille aided Fry, but otherwise the State Department obstructed Fry’s work; it wanted to protect America’s neutral diplomatic status, as well as keep American borders closed to refugees. After his forced return to the United States, Fry wrote a hard-hitting article, “The Massacre of Jews in Europe,” for The New Republic, but this, like other reports, failed to soften American refugee policy.

What Orringer Imagines About Varian Fry

By several accounts, and according to Fry’s son, Fry was a gay man at a time when it was impossible to lead an openly gay life. To show how agonizing this was, Orringer invents a past lover, Elliot Grant, who finds Fry in Marseille and asks for help in saving a friend’s son. Soon Fry and Grant have rekindled their secret romance, and Fry is questioning the morality of his mission to rescue prominent intellectuals. The fictional Fry ponders whether human beings are less worth saving if they can’t “write a perfect novel or make an enduring painting.”

Some reviewers have criticized Orringer for fictively speculating about Fry’s inner life, claiming that recent history, particularly Holocaust history, should not be muddied. In response, Orringer contends that a novelist may delve beneath the historical record in search of truths that a person couldn’t tell during his or her lifetime. Orringer’s fictional inventions are not history, but she hopes they help illuminate history as well as human complexity. The Flight Portfolio succeeds splendidly on both counts.