Anyone Out There?

April 15, 2021 in Library Corner

By Robin Jacobson.

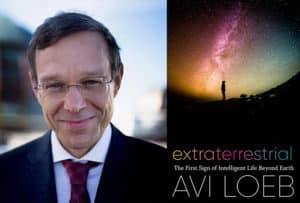

The bestselling new science memoir, Extraterrestrial: The First Sign of Intelligent Life Beyond Earth by Avi Loeb, probes a thrilling possibility – that a mysterious object that streaked through our solar system in 2017 came from an alien intelligent civilization. Avi Loeb is a world-famous astrophysicist and longtime Harvard professor. Yet as Extraterrestrial recounts, Loeb’s early focus was not on the starry heavens, but squarely on the earth and soil of his family’s Israeli farm.

The bestselling new science memoir, Extraterrestrial: The First Sign of Intelligent Life Beyond Earth by Avi Loeb, probes a thrilling possibility – that a mysterious object that streaked through our solar system in 2017 came from an alien intelligent civilization. Avi Loeb is a world-famous astrophysicist and longtime Harvard professor. Yet as Extraterrestrial recounts, Loeb’s early focus was not on the starry heavens, but squarely on the earth and soil of his family’s Israeli farm.

Loeb’s service in the Israel Defense Forces was what led him to astronomy, to research into extraterrestrial life, and to his concern that scientists have become too narrow-minded and career-focused to recognize plausible evidence bearing on one of humanity’s biggest questions – is there anyone else out there?

On the Pecan Farm

Born in 1962, Loeb grew up on his family’s farm in Beit Hanan, a small moshav (communal village) south of Tel Aviv. The Loeb farm was renowned for its pecan trees – Avi’s father was head of Israel’s pecan industry – but the family also grew oranges and grapefruit and raised chickens. Starting at a young age, Avi collected eggs every afternoon. At night, he was not stargazing, as one might imagine, but pointing a flashlight downwards, “hunting down fluffy chicks that had escaped from their cages.”

Early on, Loeb became interested in philosophy. On weekends, he would drive the tractor to a quiet spot to read the works of existentialist philosophers. But Loeb postponed life as a philosopher for mandatory army service. Selected for an elite military program for gifted students, Loeb combined soldier training with the study of physics and mathematics at Hebrew University and defense-related research.

When Loeb was only 24, he earned a Ph.D. in plasma physics. A career in philosophy still appealed to him, but he wondered whether becoming a scientist might put him in a better position to pursue answers to the fundamental questions that fascinated him. Moreover, opportunities at Princeton and Harvard beckoned. If they didn’t work out, Loeb reasoned, he could always return to philosophy or go back to the family farm. And so, Loeb became what he describes as “a somewhat accidental astrophysicist.”

Encountering ‘Oumuamua

On October 19, 2017, and for the next eleven days, astronomers first in Hawaii and then around the world observed with growing excitement the first interstellar object detected in our solar system. Scientists named the object ‘Oumuamua, a Hawaiian word loosely translated as “scout” or, in the stirring translation of the International Astronomical Union, “a messenger from afar arriving first.”

Loeb writes that every scientist who has studied ‘Oumuamua agrees that this curious visitor was highly unusual in its shape, brightness, and trajectory. For reasons explained in Extraterrestrial, the simplest explanation to Loeb for the object’s tantalizing peculiarities is that it was “created by an intelligent civilization not of this Earth.” Loeb explores the possibilities that ‘Oumuamua might be extraterrestrial junk, like a used plastic bottle adrift in the sea, or equipment, like a buoy, that outlived its purpose.

To Loeb’s dismay, many scientists refuse to engage seriously with his hypothesis, dismissing it as science fiction. Instead, they favor more ordinary-sounding explanations (e.g., ‘Oumuamua was an interstellar rock) that Loeb deems far less statistically likely. Although today’s scientists revere Galileo, the 17th century astronomer who bravely put forth evidence that Earth revolves around the sun, Loeb worries that they act more like Galileo’s antagonists, who reportedly refused even to look through his telescope before condemning him.