While the Pope Stood Silent

October 1, 2022 in Library Corner

By Robin Jacobson.

Early Shabbat morning, October 16, 1943, Nazi soldiers stormed Jewish neighborhoods in Rome, rounding up terrified Jews. They imprisoned them for two days in a military college near the Vatican before dispatching over 1,000 Jews to Auschwitz. Famously, Pope Pius XII made no protest.

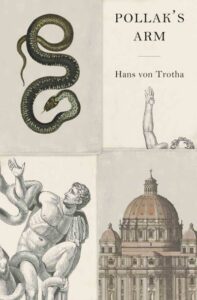

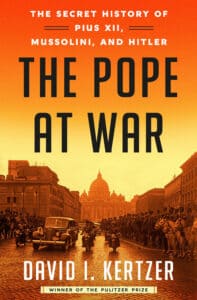

Two fascinating new books look at this moment in history and its wider context: Pollak’s Arm, a novel by German historian-journalist, Hans von Trotha, and The Pope at War, a work of non-fiction by David Kertzer. Dr. Kertzer, a renowned scholar of Vatican history, was among the first to access the Vatican’s World War II archives in 2020 after Pope Francis ordered them unsealed.

Pollak’s Arm

The action in Pollak’s Arm largely takes place on Friday, October 15, 1943, the day before the Nazi round-up. A teacher, identified only as “K,” covertly visits the Roman home of an eminent Jewish scholar, Ludwig Pollak, an actual historical person. K bears an urgent invitation from Monsignor F, a retired Vatican diplomat, for Pollak and his family to take refuge within the Vatican.

The action in Pollak’s Arm largely takes place on Friday, October 15, 1943, the day before the Nazi round-up. A teacher, identified only as “K,” covertly visits the Roman home of an eminent Jewish scholar, Ludwig Pollak, an actual historical person. K bears an urgent invitation from Monsignor F, a retired Vatican diplomat, for Pollak and his family to take refuge within the Vatican.

To K’s bewilderment, Pollak refuses to consider escaping until he has first recounted the story of his life. Pollak relates that, as a Jew, he was unable to enter academia, so he carved out a niche as an archaeologist, antiquities expert, and art dealer. During his distinguished career, he amassed honors and awards from the Vatican, the Russian tsar, the Austro-Hungarian emperor, and the German king.

Pollak reminisces about his most famous accomplishment – “Pollak’s Arm.” One of the Vatican’s prized antiquities is a monumental marble statue, Laocoön and His Sons. The statue depicts the Trojan priest Laocoön and his young sons under brutal attack by giant sea serpents. When this spectacular work was rediscovered and excavated in 1506, Laocoön’s right arm was missing. Astoundingly, four hundred years later Pollak found the missing arm (dubbed “Pollak’s Arm”); he gifted it to the Vatican. Significantly, the arm was bent backwards in agony, not raised upright heroically, like the replacement arm commissioned by the Vatican in the 16th Century.

Pollak reflects on the rich, varying interpretations of Laocoön – heroic, suffering, ensnared. Pondering his own life history through the prism of this mythic tale, he makes a choice about the Vatican invitation.

The Pope at War

Sadly, the Vatican archives have yet to yield documentation of a Vatican offer to hide Pollak – or other Jews – from the Nazi round-up. As shown in The Pope at War, the Pope made no protest to the round-up even knowing the fate that awaited Jews deported to Nazi death camps. The Vatican merely requested that the Germans release detainees that the Vatican deemed Catholic, such as former Jews baptized as Catholics.

Sadly, the Vatican archives have yet to yield documentation of a Vatican offer to hide Pollak – or other Jews – from the Nazi round-up. As shown in The Pope at War, the Pope made no protest to the round-up even knowing the fate that awaited Jews deported to Nazi death camps. The Vatican merely requested that the Germans release detainees that the Vatican deemed Catholic, such as former Jews baptized as Catholics.

Since at least October 1941, the Pope had been receiving from trusted churchmen first-hand accounts of the mass murder of Europe’s Jews. Nonetheless, when asked repeatedly by President Roosevelt’s representatives in September and October 1942 if the Vatican had information confirming the Nazis’ ongoing slaughter of Jews, the Pope declined to help. His advisor on Jewish matters had warned that if the Vatican shared its reports, the Allies might publicly cite the Vatican in support of their accusations against the Nazis.

Kertzer believes that Pius XII privately deplored the murder of Jews but elected to remain silent because his overriding priority was to protect the Catholic Church. The Pope wanted to avoid antagonizing Hitler, alienating Hitler’s millions of Catholic followers, or provoking reprisals against the Church in German-controlled territories. In the end, Kertzer says, Pius XII succeeded in safeguarding the Church, but he failed abysmally as a moral leader.