Beneath the Roman Arch

September 28, 2023 in Library Corner

By Robin Jacobson.

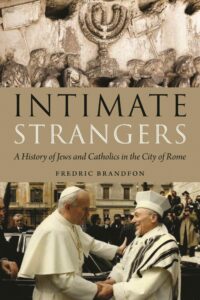

Intimate Strangers: A History of Jews and Catholics in the City of Rome by Frederic Brandfon tells the epic story of Jews in Rome across more than two millennia. It’s perfect for anyone planning to travel to Italy, armchair tourists, or history lovers.

Intimate Strangers: A History of Jews and Catholics in the City of Rome by Frederic Brandfon tells the epic story of Jews in Rome across more than two millennia. It’s perfect for anyone planning to travel to Italy, armchair tourists, or history lovers.

The book is a treasure trove of intriguing historical nuggets – Jews of Michelangelo’s time enthusiastically visiting his new statue of Moses; medieval Jews’ ritual presentation of a Torah to new popes (always rejected); the Roman Emperor’s financing of the Colosseum from the spoils of the Jewish war, and more.

The Arch of Titus

Brandfon’s exploration of the Arch of Titus (“the Arch”) is especially worthwhile. A massive monument near the Roman Forum, the Arch inspired Paris’s Arc de Triomphe and other colossal arches around the world. In this time of reappraising monuments, the Arch is a fascinating case because it can be interpreted in contradictory ways.

Emperor Domitian erected the Arch in 81 CE. to memorialize his deceased father and brother, Emperors Vespasian and Titus. The Arch honors them for their victory over Judaea and destruction of the Jerusalem Temple in 70 CE.

A famous scene portrayed on the Arch is the triumphal imperial procession through Rome in 71 C.E. As the ancient chronicler Josephus reported, Emperor Vespasian and his son, Titus, robed in purple and garlanded with laurel, led a grand parade through Rome showcasing the plundered Temple treasures. These riches included, as the Arch depicts, a magnificent seven-branched menorah. One can only imagine the misery of the Judaean captives forced to march in the spectacle.

Evolving Interpretations

For centuries, Brandfon writes, the Arch was a painful reminder to Jews of their subservient status, first under the Romans and later under the Catholic Church. During certain periods, Jews were required to greet new popes near the Arch, signifying the victory of Christianity over Judaism.

Yet on December 2, 1947, Jews in Rome surged towards the Arch. Days earlier, a historic United Nations vote approved the establishment of a Jewish state. The chief rabbi of Rome led the joyous crowd in singing Hatikvah. And then, as Brandfon movingly relates:

“[S]omething remarkable happened. Men, women, and children, waving Star of David flags, strutted beneath the arch from west to east. They were deliberately dancing in reverse, in the opposite direction from that of the Jews who were led from Jerusalem to Rome in slavery. They were symbolically undoing the events depicted in the arch, as if to say, ‘We will unravel the spool of time and erase our misfortunes of two thousand years.’” (Emphasis added.)

With the birth of Israel, some began to view the Arch as a symbol of the remarkable endurance of the Jewish people. During a Hanukkah celebration in 1997, the then-Mayor of Rome, Francesco Rutelli, remarked:

“When many people look at the sculpture under the arch, they only see the misery inflicted upon a conquered race. But look again. I see not a conquered race but a monument to one of the greatest modern nations on earth . . . the Jewish nation continues to thrive within and outside the State of Israel.”

Most telling, since 1949, the State of Israel’s official national emblem has been the seven-branch menorah, drawn to match the Temple menorah on the Arch. Symbolically, the Jews brought the menorah back to Jerusalem, redeemed from its long captivity in Rome.

The flow of history, as Rutelli’s remarks suggest, added complexity and multiple layers to the Arch’s interpretation. Once seen as a monument to Roman conquest and Jewish humiliation, the Arch now reminds viewers both of Jewish exile and return.