Music, War, and Memory

November 30, 2023 in Library Corner

By Robin Jacobson.

The great German poet-playwright Goethe had a deep fondness for a grand oak tree in the woodlands near Weimar. One autumn morning in 1827, he famously picnicked beneath its shade. A century later, when prisoners were felling trees in the area to make way for a concentration camp, the guards told them to be sure to spare that particular tree. Soon, Buchenwald buildings surrounded Goethe’s beloved oak, a bitterly ironic remnant of Germany’s reverence for culture in the most inhumane place imaginable.

The great German poet-playwright Goethe had a deep fondness for a grand oak tree in the woodlands near Weimar. One autumn morning in 1827, he famously picnicked beneath its shade. A century later, when prisoners were felling trees in the area to make way for a concentration camp, the guards told them to be sure to spare that particular tree. Soon, Buchenwald buildings surrounded Goethe’s beloved oak, a bitterly ironic remnant of Germany’s reverence for culture in the most inhumane place imaginable.

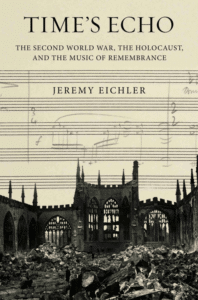

The tale of Goethe’s tree opens Jeremy Eichler’s beautiful and profound book, Time’s Echo: The Second World War, the Holocaust, and the Music of Remembrance. Eichler, chief classical music critic for The Boston Globe, also holds a Ph.D. in modern European history. Drawing on this dual expertise, he tells the story of four famous 20th century musical memorials by Arnold Schoenberg, Richard Strauss, Benjamin Britten, and Dmitri Shostakovich.

Eichler’s book is rich in myriad ways, including as a meditation on music’s transcendent power across time. Against the backdrop of the Israel-Hamas and Ukraine-Russia wars, the chapters on Shostakovich’s “Babi Yar” Symphony read with special resonance.

Breaking the Silence on Babi Yar

Babi Yar (now called by its Ukrainian name, Babyn Yar) is a former ravine on the outskirts of Kyiv and the site of a two-day German massacre of more than 34,000 Jews in September 1941. As Eichler explains, this was part of the “Holocaust by bullets, in which people were murdered not impersonally . . . but one at a time . . . with killers close enough to look them in the eyes.” In the aftermath of October 7, the face-to-face brutality of the Einsatzgruppen (SS killing squads) sounds chillingly like the Hamas massacre of Israeli kibbutzniks.

After World War II, the Soviet regime took extraordinary steps to suppress any memorialization of the Babi Yar victims, ostensibly because they did not want to “divide the dead” or separate Jewish suffering from the collective Soviet tragedy. In the 1950s, the government tried to erase the Babi Yar ravine by building a dam that flooded it with silt and muddy water. When the dam eventually collapsed, dump trucks filled the ravine with soil.

In 1961, Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich courageously set to music a poem by Yevgeny Yevtushenko that began, “Over Babi Yar, there is no monument.” Neither Yevtushenko nor Shostakovich were Jewish, but they called for their fellow citizens to acknowledge the reality of Jewish persecution.

Not till the fall of the Soviet Union was a monument to the Jewish dead installed at Babi Yar. But in March 2022, Russian missiles attacking Kyiv damaged the site. Movingly, Eichler writes that Shostakovich’s symphony is perhaps Babi Yar’s “most imperishable” monument.

Dmitri Shostakovich

Like some Russian intellectuals today, Shostakovich had a fraught relationship with his government. Alternatively honored and ostracized, he sometimes lived in luxury in Moscow and other times spent fearful nights by the building elevator so that if the KGB came to arrest him his family could sleep undisturbed.

But the Soviet people adored Shostakovich’s music. Reportedly, exuberant fans climbed through concert hall ventilation systems to hear his work. His Leningrad Symphony, performed in that city in 1942 during a 900-day German siege, not only rallied the exhausted residents, but was said to have convinced eavesdropping German soldiers that they would never conquer Leningrad.

Despite the tragedies recounted in Time’s Echo, Eichler’s book feels hopeful. “Babi Yar” and the other musical memorials capture not only the devastation of war but also yet-to-be-realized hopes for universal human solidarity. We can still recover those aspirations, Eichler says, to build a more peaceful future.