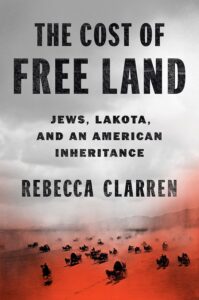

The Cost of Free Land: Jews, Lakota, and an American Inheritance

January 29, 2024 in Library Corner

By Robin Jacobson.

“Pa pleaded. “We can get a hundred and sixty acres out west, just by living on it… If Uncle Sam’s willing to give us a farm… I say let’s take it.”

Laura Ingalls Wilder (By the Shores of Silver Lake)

In 1862, Congress enacted the Homestead Act, hoping to encourage settlement of America’s Western territories. This landmark legislation promised 160 acres of free federal land to eligible persons, including immigrants who declared their intention of becoming citizens. Rebecca Clarren’s Jewish immigrant ancestors were among thousands who headed West to take advantage of this grand offer.

In 1862, Congress enacted the Homestead Act, hoping to encourage settlement of America’s Western territories. This landmark legislation promised 160 acres of free federal land to eligible persons, including immigrants who declared their intention of becoming citizens. Rebecca Clarren’s Jewish immigrant ancestors were among thousands who headed West to take advantage of this grand offer.

Clarren grew up with stories of her homesteading forebears’ bravery and grit. With hard work, they became financially successful, elevating themselves and their descendants to the American middle class. But in recent years, Clarren, an investigative reporter who specializes in the American West, discovered that her family’s good fortune came partly at the expense of Native Americans.

Her family’s “free land” had been the home of the Lakota people for hundreds of generations before the United States seized it and made it available to homesteaders. Uncertain what to think or do, Clarren turned to Jewish texts for guidance. She relates this compelling story – part history, part memoir – in The Cost of Free Land: Jews, Lakota, and an American Inheritance.

The Shtetl on the Prairie

Fleeing pogroms in Czarist Russia, Clarren’s family, the Sinykins, escaped to America in the late 19th century. Exhilarated at the prospect of “free land,” they set off to remake their lives in South Dakota.

The Sinykins settled in an area with other Jewish settlers that became known as Jew Flats. They had their own rabbi, who also served as a shochet, a Jewish butcher able to provide the community with kosher meat. For a mikvah, Clarren’s great-great-grandmother dunked in the creek behind the house, even in the icy winter.

The Sinykins may or may not have realized that Jew Flats had been the age-old home of the much-persecuted Lakota. At the hands of the American government, the Lakota endured multiple massacres, forced displacement, broken treaties, land theft, and the mass slaughter of the buffalo, a main source of food.

A Path to Repair

Clarren shared her concerns about her homesteading ancestors with a revered Native American judge. Although Clarren’s forebears had not harmed the Lakota directly, they and their descendants benefited from the government’s taking of Lakota land. The judge advised Clarren to study the traditions of her own people, the Jews, on what constitutes harm and how to make it right. “Justice works best,” said the judge, “when it is grounded in one’s own culture.”

Taking this counsel to heart, Clarren embarked on several years of Jewish text study with her rabbi. They were struck by a Talmudic passage describing a dispute over what should be done if a stolen beam was used in erecting a building. The House of Shammai opined that the building must be demolished so that the beam could be returned to its true owner. In contrast, the House of Hillel had a more pragmatic solution – leave the building standing, but reimburse the beam owner for its full value. The disputants completely agreed, however, that amends must be made for the stolen beam.

The Cost of Free Land reveals how Clarren applied this and other Jewish teachings to her family’s situation. Beyond that, the entire book, Clarren says, “can be read as a land acknowledgement to the Lakota nation.”