Looking Anew at Captain Dreyfus

April 8, 2024 in Library Corner

By Robin Jacobson.

Near the turn of the 20th Century, the Dreyfus Affair thrust France into turmoil. In 1894, the French army falsely accused and convicted Jewish military captain Alfred Dreyfus of treasonously selling military secrets to Germany. In a humiliating public ceremony, Dreyfus was stripped of his military insignia and his sword broken while crowds shouted, “Death to the Jews.”

Near the turn of the 20th Century, the Dreyfus Affair thrust France into turmoil. In 1894, the French army falsely accused and convicted Jewish military captain Alfred Dreyfus of treasonously selling military secrets to Germany. In a humiliating public ceremony, Dreyfus was stripped of his military insignia and his sword broken while crowds shouted, “Death to the Jews.”

Imprisoned on Devil’s Island (off the coast of South America), Dreyfus relied on his family and supporters to amass proof that he was innocent and that another army officer was the actual traitor. As reports of an army cover-up leaked to the press, France divided into Dreyfusard and anti-Dreyfusard camps. Antisemitic riots broke out across France.

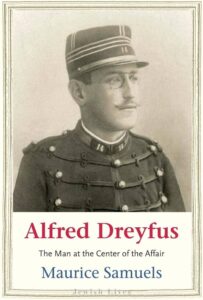

The Dreyfus Affair continued for twelve tumultuous years until Dreyfus was finally exonerated in 1906. It has been the subject of countless books, but Alfred Dreyfus: The Man at the Center of the Affair by Maurice Samuels, focuses on Alfred Dreyfus himself rather than just the “Affair.” A Yale University French professor, Samuels is also the director of the Yale Program for the Study of Antisemitism.

Patriotism and Fortitude

Alfred Dreyfus (1859-1935) was born in the French province of Alsace, where his family had deep roots, stretching back hundreds of years. Dreyfus’s father, Raphaël, made the family’s fortune by opening a cotton mill in Mulhouse, Alsace, a center of France’s textile manufacturing industry.

In 1870, when Dreyfus was a child, he saw Prussian troops march into Mulhouse during the Franco-Prussian War. After the French defeat, Germany annexed Alsace. As a fervently patriotic young man, Dreyfus joined the army, hoping to someday serve in a campaign that would wrest his home back from Germany.

Throughout his brutal imprisonment on Devil’s Island, Dreyfus steadfastly believed that the French justice system would vindicate him. Shackled to his bed, beset by heat, insects, malnutrition, and illness, Dreyfus resisted the impulse to simply give up, stop eating, and let his life ebb away. He was determined to live to restore both his own honor and that of France. Without his heroic fortitude, there would have been no revelation of the falsity of the accusations against him or the army’s nefarious cover-up.

Dreyfus and Judaism

To Dreyfus and others of his milieu, says Samuels, “Frenchness and Jewishness went hand in hand.” As citizens of the first modern European nation to eliminate legal restrictions against Jews, Dreyfus and his circle, writes Samuels, “felt doubly French” because it was their emancipation after the French Revolution that elevated France to a nation committed to equal rights.

As “French men and women of the Mosaic persuasion,” the Dreyfus family felt similar in every respect to other French families, says Samuels, except with regard to worship. Judaism was an important, but private, aspect of their lives.

Contradictory Take-Aways

As Samuels shows, political groups interpreted the Dreyfus Affair to validate their own convictions. To the budding Zionist movement, the false accusation of Dreyfus, and the accompanying surge of antisemitism, proved Jews needed their own homeland because they were not safe even in supposedly enlightened France. In contrast, those who believed that Jews should integrate into the nations where they lived were reassured by France’s exoneration of Dreyfus.

The Dreyfus Affair remains a powerful example of the way antisemitism morphs to reflect the concerns of the time. French citizens made uneasy by modernization, capitalism, and the departure from traditional Catholic values blamed Jews for what they saw as society’s ills. Sadly, even in 2024, antisemitism continues to shape-shift and to portray the perceived ills of our time as the fault of the Jews.