The Madwoman in the Rabbi’s Attic

September 12, 2024 in Library Corner

By Robin Jacobson.

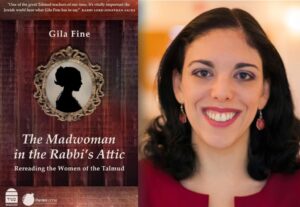

Each High Holiday season, we turn again to sacred texts in search of new insights. That makes this a fitting time for Gila Fine’s The Madwoman in the Rabbi’s Attic: Rereading the Women of the Talmud. Fine takes a fresh and fascinating look at six stories in the Talmud, positing that the women who seem to be the stories’ villains may actually be their heroines.

Each High Holiday season, we turn again to sacred texts in search of new insights. That makes this a fitting time for Gila Fine’s The Madwoman in the Rabbi’s Attic: Rereading the Women of the Talmud. Fine takes a fresh and fascinating look at six stories in the Talmud, positing that the women who seem to be the stories’ villains may actually be their heroines.

Fine, the former editor in chief of Maggid Books, is a lecturer of rabbinic literature at the Pardes Institute of Jewish Studies, and serves on the faculties of several other prestigious institutions. Haaretz has called her “a young woman on her way to becoming one of the more outstanding Jewish thinkers of the next generation.”

A Heartbroken Twelve-Year-Old

Fine opens Madwoman with a childhood memory of an afternoon at her grandparents’ home in London. Told to write her bat mitzvah speech, she flipped through the classic Book of Legends, edited by Hayim Bialik. Perusing the category of “woman,” she was heartbroken to discover that the rabbis of the Talmud, whom she had been reared to revere, viewed women as weak, irrational, greedy, petty, promiscuous, and vain.

Many years of religious struggle and study followed. Fine says that she finally made peace with – and found joy in – the Talmud by learning to read it more deeply. This approach did not, of course, transform rabbis rooted in patriarchal societies into 21st century feminists. Nonetheless, Fine discovered that the rabbis’ “moral lessons about how to treat the Others in our midst” sometimes embedded portrayals of complex and admirable women.

The Shrew Who Wasn’t a Shrew

Fine focuses on six women named in the Talmud who have their own stories. One of the most intriguing is Yalta, the wife of Rav Nachman. At first reading, Yalta seems an archetypal shrew, easily triggered into angry outbursts.

In the story, Rav Nachman entertains a visitor, Ulla. After the men dine, Ulla makes the concluding blessing. Rav Nachman suggests that they send the cup of wine used in the blessing to Yalta so that she might also sip from it and be blessed. Ulla objects, saying that women receive blessings through their husbands, not independently. As Fine shows, the biological understanding of that time regarding the blessing of childbirth was that men furnish the essential essence – the seed – of a future child while women are simply containers or receptacles for that seed.

Overhearing Ulla’s refusal to send the cup, Yalta immediately goes to the storeroom. Seemingly convulsed with anger, she smashes 400 jars of wine. Yet Fine evinces evidence that, far from throwing a temper tantrum, Yalta is deliberately making a point. Yalta is demonstrating that vessels are essential – if a wine bottle is smashed, the wine it contained is ruined and undrinkable.

Why aren’t the Talmud’s teachings explicit?

One might challenge Fine’s search for hidden meaning in the Talmud text by asking why the rabbis would choose to engage in riddles or puzzles. If the moral lesson from Yalta’s story, for instance, is that women deserve respect, why not just make that lesson explicit?

Fine responds that Yalta’s story and others in Madwoman “show us how apt we are to misinterpret and how dangerous such misinterpretation can be.” The stories “force us to look below the surface” when meeting a character on the page and encourage us to do the same with the marginalized “Others” we encounter in daily life. In Fine’s view, analyzing the stories gives us practice in being more sensitive, humble, and empathetic. These qualities help us to live morally, the rabbis’ ultimate aim.